Overview and Concept

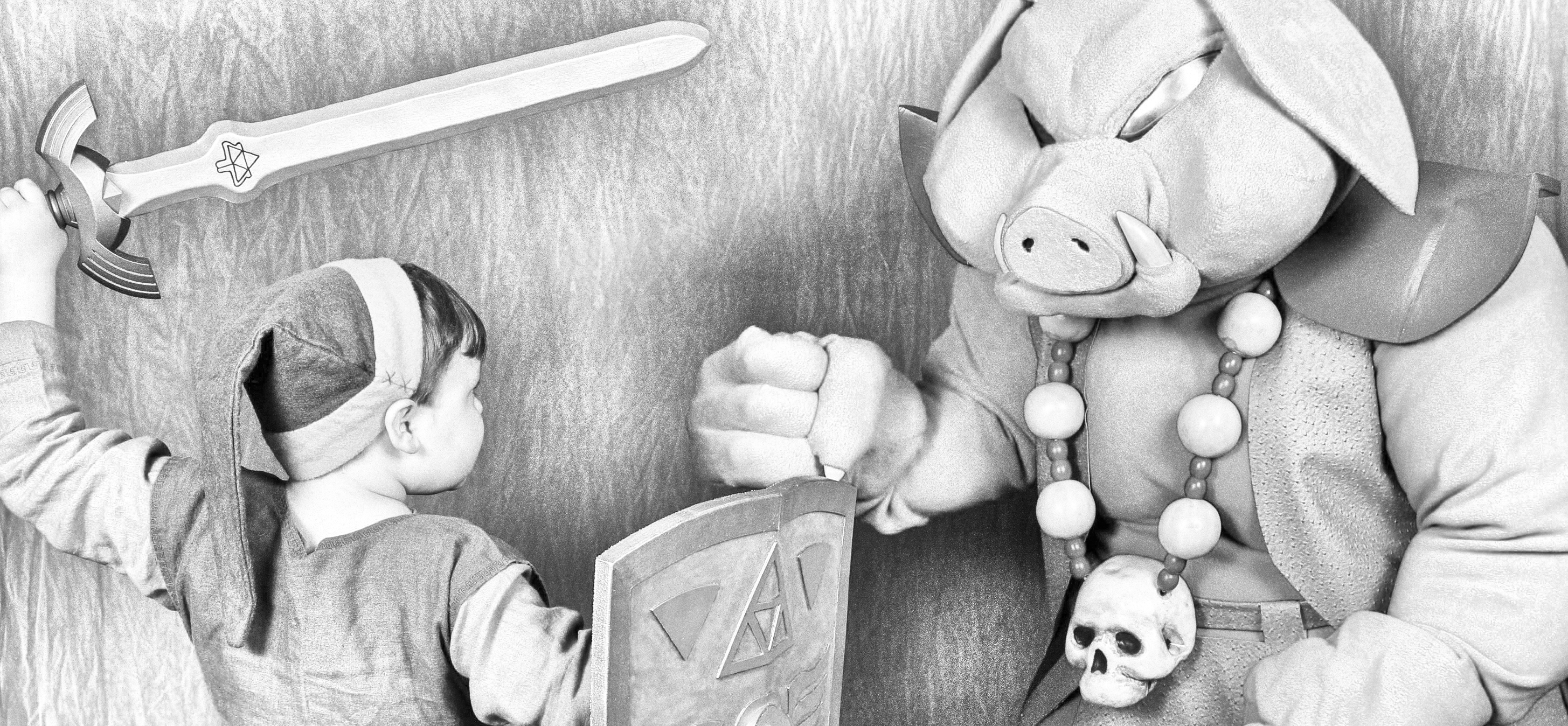

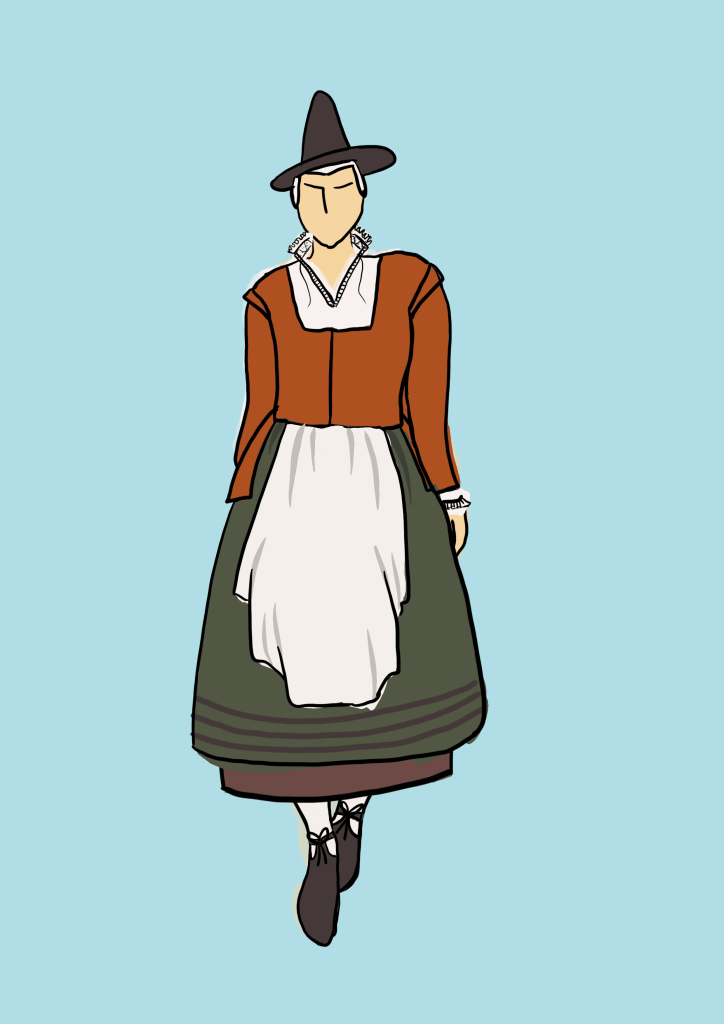

When I began my project of making a “historical” witch costume, I chose to focus my research on the Jacobean period in Great Britain. Prior to ascending to the English throne, King James I printed a treatise in 1597 entitled Daemonology, endorsing the practice of witch hunting. Slightly later, during the English Civil War, Matthew Hopkins, self-professed “Witchfinder General” and author of The Discovery of Witches, sent more people to be hanged for witchcraft than any witch hunter in England in the previous 160 years. Bookended by these two publications, I searched for documentation of women’s dress roughly between the years 1600-1640.

Inspiration was taken from early-17th century illustrations of working women and witches, as well as extant garments. Black was a signifier of wealth during this period (as truly black garments required intensive dying) and the more traditional choice for witches; however, the ensemble’s color palette was chosen to reflect earthy tones of brown, green, and orange, readily available through natural dyes. Likewise, natural fibers of linen were chosen for the waistcoat fabric, thread, lace trim, linings, and accessories, while wool was employed for the kirtle, embroidery, and kirtle trim.

Click on images to enlarge.

Kirtle

A kirtle was an underdress worn by English women of many classes from the late middle ages until the 17th century. It was more common with the lower-classes by the end of its tenure, but was extremely versatile and could be layered to achieve many fashions. It featured a full skirt and a tight, lace-up bodice designed to provide support. Eventually its use gave way to stays or jumps reinforced with whale bone, the forerunner to historical corsets

This kirtle is modified from a pattern by Tudor Tailor to have side lacing, rather than the more common front lacing. This choice was made to prevent the kirtle lacing from interfering with the waistcoat above it, and to increase the garment’s adjustability. Lacing in this period was done in the spiral style, which is much easier to tighten than typical modern cross-lacing. The kirtle is cut from green wool serge, a kind of lightweight twill, and reinforced with several lining layers of unbleached linen canvas, padstitched together. All seams were hand-sewn with waxed linen thread in the style of the period, by hemming each piece and then joining them via casting stitches. A “guard” trim of brown wool felt was added at the bottom edge of the skirt.

Click on images to enlarge.

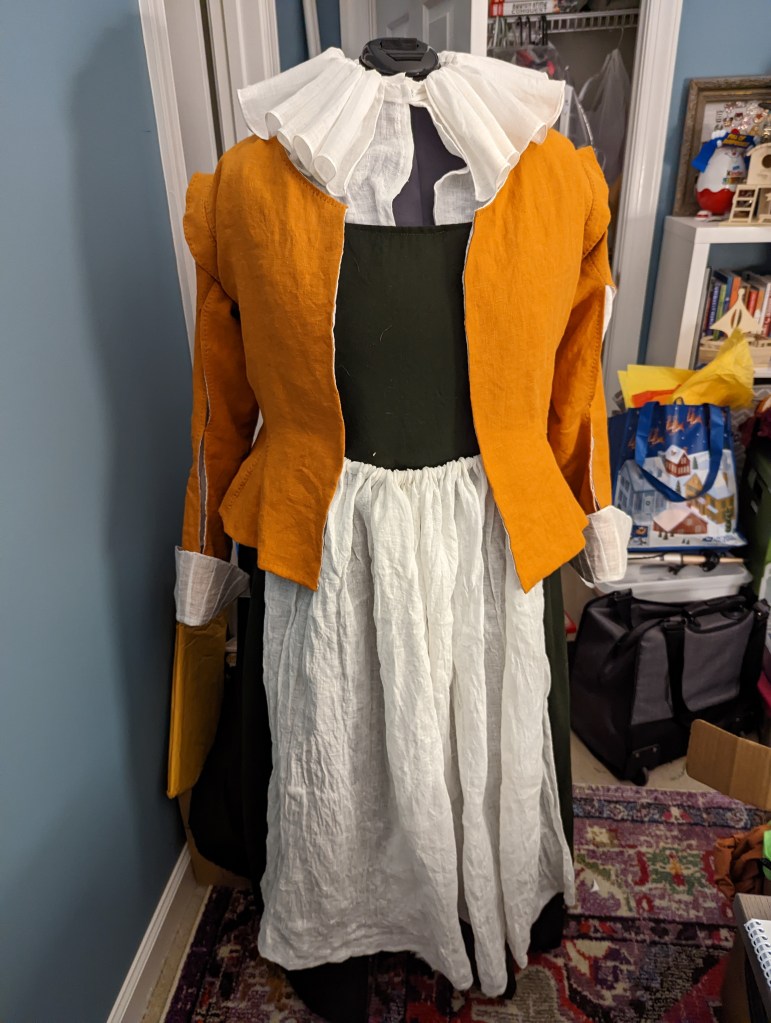

Waistcoat

Waistcoats were a universal layer for the upper and working classes in the early 16th century, in varying materials and levels of decoration. Along with wool and silk, linen was a common waistcoat fabric, especially as a canvas for the extravagant polychromatic embroidery characteristic of the period.

This waistcoat was modified from the Tudor Tailor pattern to have armscyes set lower on the shoulder and a higher waist than was typical for the preceding Tudor period. Stitching was done by hand, as with the kirtle, in waxed linen thread in the style of the period. Silk ribbons were sewn at intervals along the front to serve as closures, following several paintings and extant examples. Hand-made, brown linen lace was added along the front opening and the wings, as was seen in extant pieces.

Click on images to enlarge.

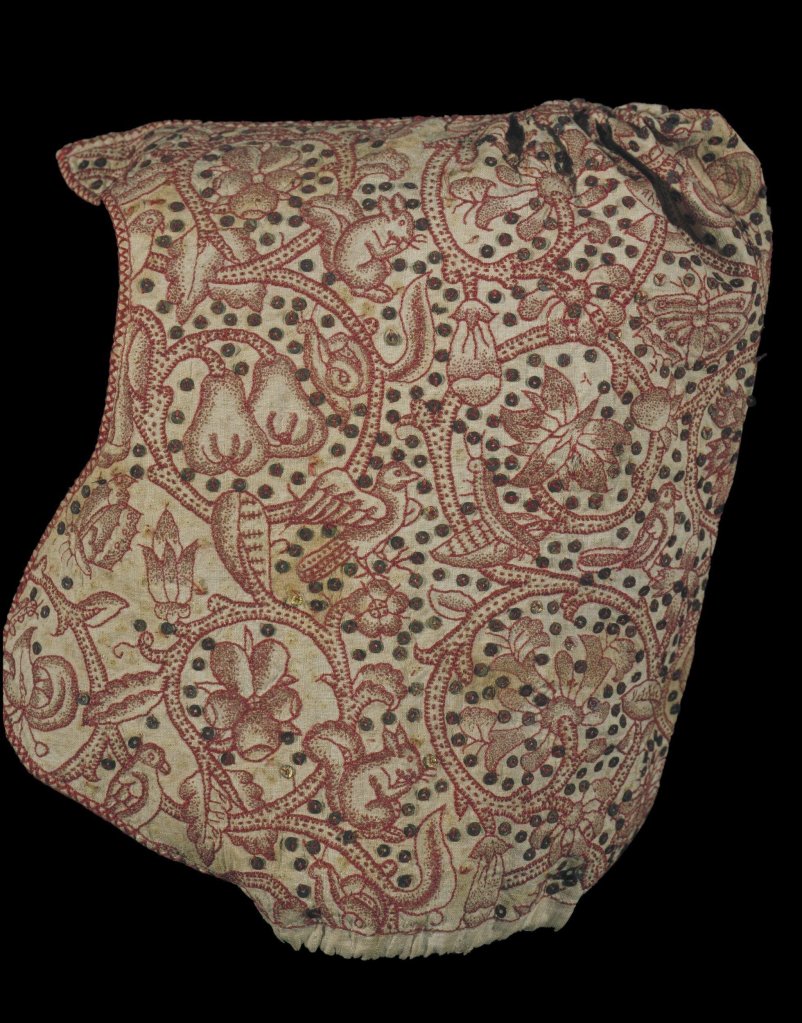

Coif

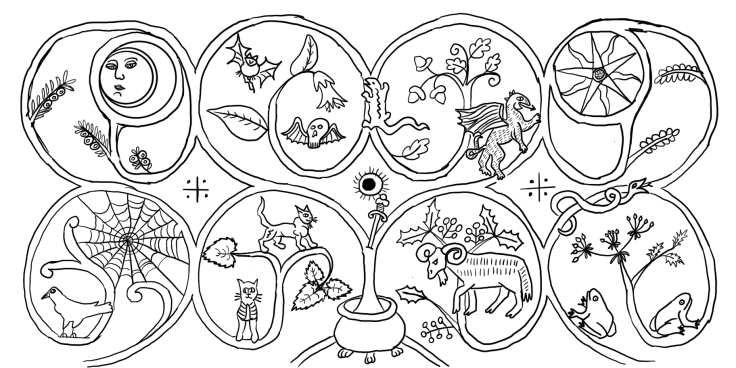

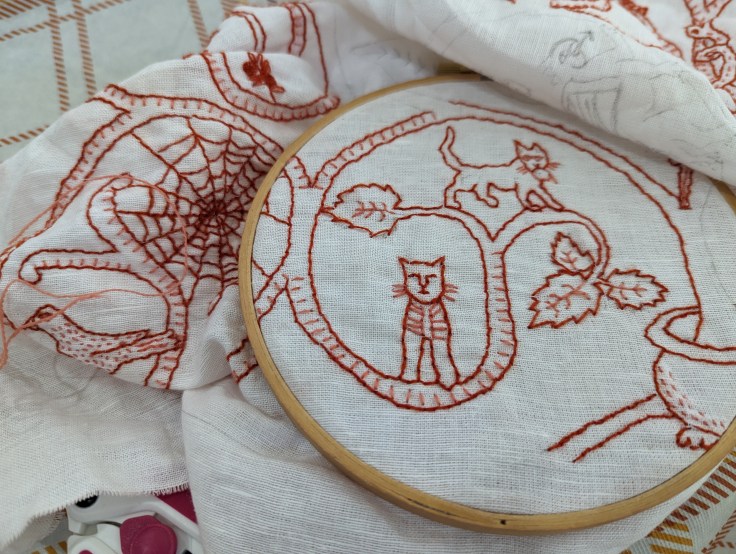

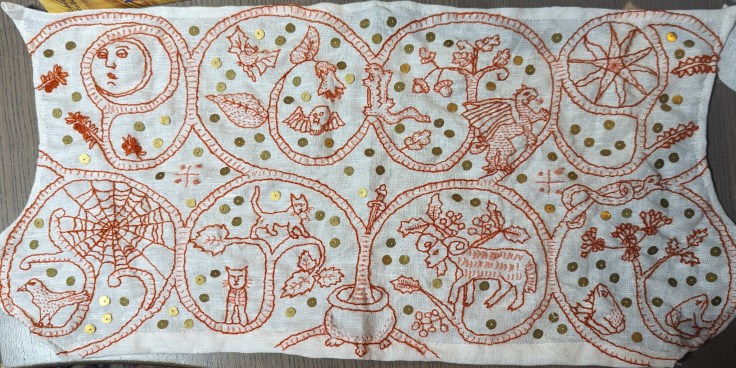

No woman of the Jacobean period would have left the house without a head covering, and linen coifs or caps were worn even underneath hats. For a working woman, a coif would not only ensure that her hair were modestly covered, but also served to keep it clean during chores or travel. Extant coifs from the early 17th century are highly decorated with lace, embroidery and spangles–perhaps worn by wealthier women, or on special occasions. Books of embroidery patterns were common in the Jacobean period, and examples of printed pattern pages that have been pricked for pouncing with graphite or chalk to transfer the pattern to the cloth still exist.

The pattern for this coif was made by studying the shape and dimensions of the copious numbers of extant garments documented by various museums. The decoration was designed by the artist with witchcraft iconography inspired by the recipes of Shakespeare’s Weird Sisters and illustrations from period books. Natural elements of flora and fauna were most common in the embroidery of the period. Two colors of madder-died wool were worked in Holbein stitch and seed stitch for a monochromatic effect, and brass spangles were added with three stitches, as seen in an extant piece. Following the historical process, the pattern was transferred to a suitably-sized piece of linen and then embroidered, before being cut out and stitched together. Gathering stitches at the crown and a channel for a tie of linen tape shape the coif. Handmade lace trim of linen was added around the facing.

Click on images to enlarge.

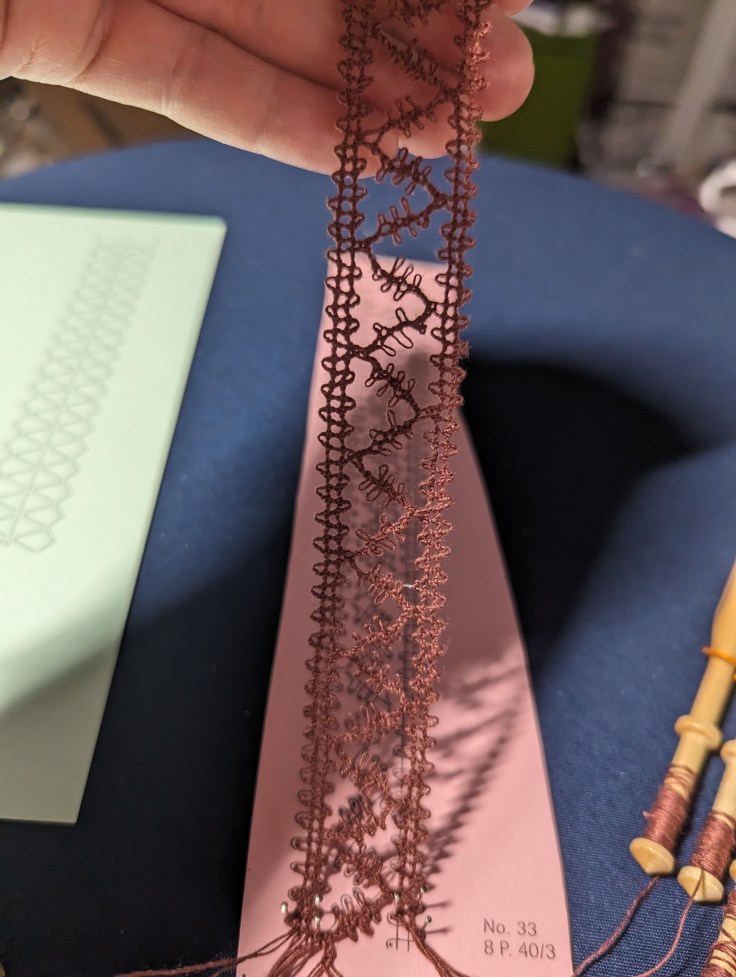

Lace Trim

Modern lace came to fashion in 15th century Italy, and soon spread across the European continent. Many centers of lacemaking rose across the Renaissance and Baroque periods, each with their own methodology and designs. Lace in the Jacobean period was typically needle lace, worked on pulled-thread linen, but bobbin lace had also been in development for over a century. Much like with embroidery, books of fashionable designs in the form of woodblock illustrations were printed and shared, though not many of these sources remain.

Two of the laces for this project were taken from the Nüw Modelbuch, the first lace pattern book published in the German language in 1561. The other design, featured on the sleeve wings, was developed by the artist. While lace was typically worked in white linen or silk, brown linen thread was chosen for the waistcoat trim, following other colors of linen lace found on extant waistcoats. Of course, lace was often worked in metallic threads, but this was both an expensive and technically advanced option.

Click on images to enlarge.

Accessories

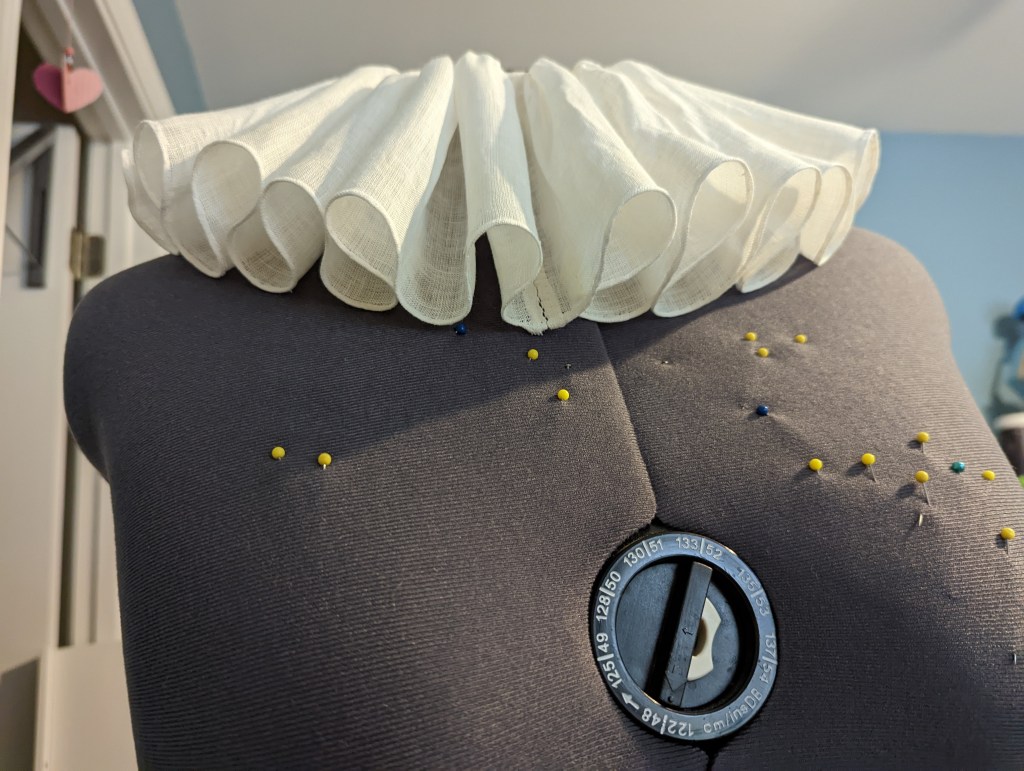

No ensemble would have been complete without certain accessories during the Jacobean period. A base layer underneath all clothing would have been white linen chemise or shirt, easy to wash, and to protect both the skin underneath and the more expensive layers above. It is very easy to draft a chemise from your body measurements, employing rectangles that minimize fabric waste. I included underarm gussets and a high collar with split neckline for modesty.

The ruff was constructed by first hemming one side of a 3.5 yard strip of handkerchief-weight linen, and then stroke gathering the other side. This was then stitched, gather by gather, to linen tape, and encased in a neck band. After stitching, the ruff was starched and ironed with a modern, conical-shaped hair iron. The apron was constructed of the same linen, with a similar technique.

The shoes are leather latchet shoes purchased from American Duchess. Silk ribbon with brass aglets were added as laces, following examples in period portraiture. The hat is wool felt, purchased from an artisan in Spain, with the addition of wool felt leaves at the upturned brim. While this style of hat has no support from primary sources, it is evocative of the traditional witches’ hat.

Click on images to enlarge.

Additional Resources:

Bullat, Samantha, Couture Courtesan, https://couturecourtesan.blogspot.com/, 27 Jan. 2024.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Collections https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search

Mikhaila, Ninya, and Jane Malcolm-Davies. The Tudor tailor: Reconstructing sixteenth-century dress. Batsford, 2006.

North, Susan & Tiramani, Jenny (eds.), Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns: Book One, V&A Publishing, 2011.

North, Susan & Tiramani, Jenny (eds.), Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns: Book Two, V&A Publishing, 2012.

The V&A Museum Collections https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections